Math and Music Courses Provide a Symphony of Learning

Math and Music and The Study of Video Game Music courses explore how concepts within math and music foster a better understanding and appreciation for both disciplines.

From counting the beats in musical measures to the sounds that accompany video game soundtracks, music and mathematics have a symbiotic relationship. The two fields are intertwined, which is the idea behind two courses — Math and Music and The Study of Video Game Music — offered through Rose-Hulman’s Humanities, Social Sciences and Arts (HSSA) department in cooperation with the Mathematics department. HSSA courses give students the tools to think critically and creatively about culture and society.

“Music needs engineers, and engineers need music,” said Associate Professor of Music David Chapman, PhD. “These courses provide more than one thing to students. Engineers are whole people and courses like these provide practical and meaningful application for their humanities studies.”

Chapman, who is in his tenth year of teaching music at Rose, has worked to make the field of musicology ever more relevant to students. This means teaching not only courses like Baroque, Classical, and Romantic Music, but also mathematics and music, or film music, or video game music, because these types of courses bridge the gap between music studies and where the students are in their own life.

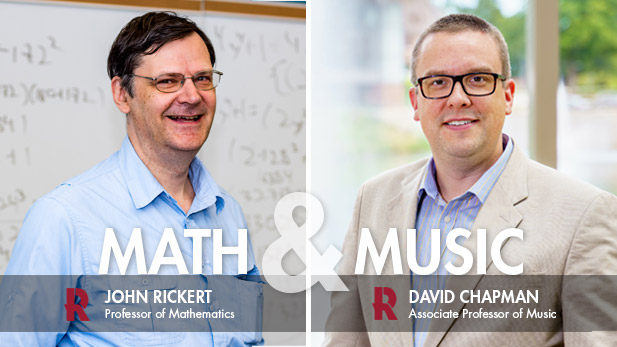

The Math and Music course has been offered twice and is a collaborative effort between Chapman and Professor of Mathematics John Rickert, PhD. Rickert believes that while Rose students are very technical, many have an interest in music. As such, he saw a natural collaboration between himself and Chapman.

“Classes like this help broaden the students,” said Rickert. “Many of them are very interested in music in different ways. The class gives them a better appreciation for the nuances and a different view on the technical aspects.”

Senior Kiera Chapuis believes the Mathematics and Music course was a great example of co-teaching, and felt the concepts helped in her major of mechanical engineering.

“I learned a lot about frequencies in this class,” said Chapuis. “It was great for building an understanding of string tensions, various frequencies of tubes, and ways those things make music. We also did a lot of set theory, geometric series, and learned some mathematical models that relate to music.”

The premise behind the class was that music and math are useful lenses for understanding each other. Rickert and Chapman approached the class as a way to use musical concepts to understand mathematical principles. Numbers, patterns and shapes can be part of the metaphors used to explore the basis of musical creativity. The class focused on mathematical underpinnings of music, how it’s created and the physics behind music. Students also learned how discrete mathematics — integers, graphs and statements in logic — are applied to and shape music for a more artistic view of math.

“In music, we do a lot of counting,” said Chapman. “Counting seems easy because that’s what we start with in life, in kindergarten. When you apply counting to music it can become a very challenging task. The simplest mathematical concepts can be very complex when applied to music and vice versa. You think you know everything about simple math and then apply it to music and it reveals a deep world to explore.”

For their final course projects, students selected topics where math and music play integrated roles. Some students focused on concepts such as acoustics and fractal music. Others used integer notation to discuss pitch or the formation of scales, chords or tuning systems, as well as music in different cultures, the construction of instruments and the mapping of different geometric sequences in music.

“Many of the students in the class had some background in one or both topics, so it was really fun to bridge the gap between the two,” said Chapuis. “Sometimes people are a little more visual, so seeing things in terms of music can actually be helpful to their understanding of the math. Alternatively, sometimes people can be more number oriented which can make music a bit more challenging, so seeing the two mediums side by side can help a lot.”

Chapman also taught a class on ludomusicology, an emerging field that studies video game music. Much like the mathematics and music course, this course was extremely popular among Rose students. For Chapman, who was himself a gamer in his childhood and teenage years, teaching this class was also a very collaborative effort, between him and the students.

“I bring a historical approach to the class, while the students bring a very current relationship to video games and their expertise as engineers, math majors and people who think in gaming,” he said.

The class looked at video game music through a historical lens, starting with games in the 1960s and 70s that did not have programmed audio components. From there, they worked forward in history, examining each gaming era and their methods for using music in games. Students also explored how video game music is a special type of language that is partially programmed by video game creators, but also by the experience of the player.

“In video games, music responds to the player in various ways, which challenges the traditional notions of audience and composer,” said Chapman. “Video game music is participatory, and the musical experience is different every time you engage and complete the game. … These are unique musical experiences you find in very few other areas of culture.”

Students finished the class with a research project that focused on video game music. Some students performed game music live, while others studied a game and showed how the music helped tell the game’s story. Chapman believes this type of class is not just about engineering and music, but how HSSA classes are relevant to engineers.

“I had a student on their evaluation write that this was the first time (they) felt like a scholar,” said Chapman. “That’s one of the greatest student comments I’ve ever received, and I think it’s because students were able to bring together a personal passion with their academic studies.”