Biology Student Advances Understanding of “Magnetic Bacteria"

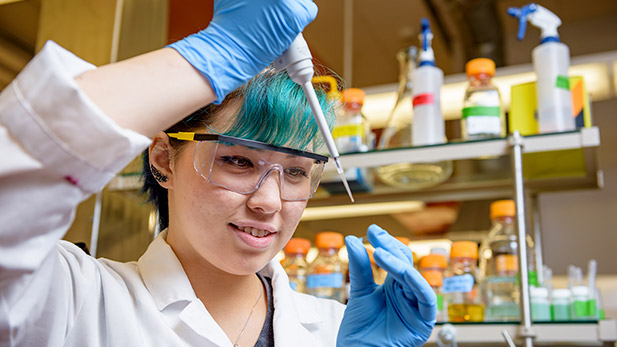

Madeleine Pasco's research is exploring magnetic bacteria and the organism's response to the earth's magnetic field.

Madeleine Pasco steps directly into the Wabash River, its murky brown water swirling around her rubber rain boots. Holding a lab beaker like a shovel, she bends to scoop sediment from the river’s floor, collecting the slimy mud she hopes contains “magnetic bacteria” often found in the muck at the bottom of bodies of water all around the world.

Collecting samples in this way—something she repeated at two nearby lakes—was just one part of a months-long research project aimed at better understanding single-cell, microscopic organisms with tiny iron crystals inside them known as magnetotactic bacteria.

Back in Olin Hall, Pasco adjusts a high-powered microscope outfitted with a special device created by physics and mathematics student Jacob Guttman that allows her to expose the bacteria to magnetic fields and observe the results. It’s not as easy as it sounds. The bacteria are clear so it can be difficult to distinguish them from the water around them, and keeping them under the viewer is sometimes difficult.

“It’s frustrating and then it’s rewarding and that’s when it’s worth it,” she says.

One big question Pasco, a biology major, wants to explore is whether these bacteria respond to the earth’s magnetic field. One theory is that the organisms use their tiny pieces of iron like a compass, helping them navigate underwater as they search for the most hospitable places to call home. Too little, or too much, oxygen can be fatal to these tiny creatures, so finding the right place to settle is a matter of life and death, she explains.

But testing this theory is no easy feat. Living organisms—even very simple ones—often don’t behave in predictable, easy-to-understand ways, she says. And these bacteria are no exception. Exposed to magnetic currents, most of them move as Pasco expects, others don’t move at all, and some move in the opposite direction.

An experienced researcher, Pasco takes this in stride.

“The interesting thing about science is that no one else has the answer. You just have to keep failing until you don’t fail anymore.”

Pasco, who has done research each of the past several summers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Maryland, is a firm believer in the value of basic scientific research, even when the immediate practical results are unclear. Doing basic research teaches people the right way to do science, she notes. And, she adds, big discoveries don’t happen without basic research laying the groundwork.

“People have lots of reasons for doing basic research,” she explains. “I do it because I think it’s really cool.”

Looking up from her neatly printed research notebook, Pasco, whose work this summer is funded by a Weaver grant, explains she may pursue a Ph.D. after graduating in February, but that’s not yet certain. A member of several clubs on campus and active in her sorority, she has a wide variety of interests and is keeping her options open. Like the bacteria she studies, it’s not clear what she’ll do next.